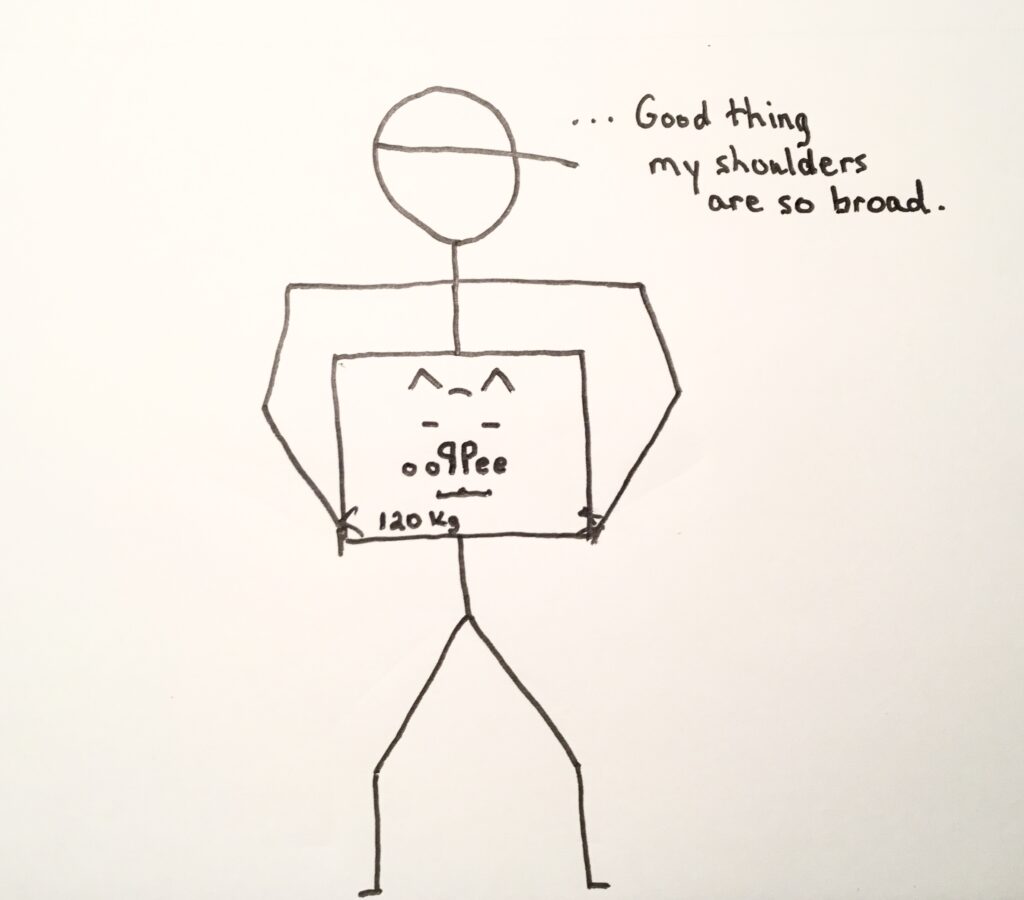

I had never been to a Costco before last week. The place does not interest me. But as people seem to regard me with undisguised suspicion when I say that, I thought I should use the fact that my sister was dragging me there to help carry an awkward 20 kg. box of cat litter. It would be an opportunity to broaden my horizons. And my shoulders.

I anticipated a writer’s quest to observe, perhaps understand, maybe use in some way, a quick reference in a hypothetical Chapter Six down the line.

Hearsay plus my imagination had sketched a version of this reality. I was prepared to put it up against my observations. I needed to know how far off I would have been if I had not set foot in one and written about it anyway.

I would have been way off. It was so much worse than I had imagined and, at the same time, so much better.

Funnelling past the membership sentries at the garage door entrance, I dutifully tailed my sister closely, and there at the threshold held my breath, the space I perceived at once evoking feelings of both claustrophobia and agoraphobia. There was row upon row of stacked boxes preventing me from seeing any distance. At the same time, the starkly white ceiling over my head soared many stories high, empty space to spare. As I navigated this contradiction, I had to be careful not to spend too much time gaping slack-jawed at the profusion of single-item displays, the towers of TVs, the pyramids of pyjamas, lest I be run over by a bargain-hunting scavenger who knew their way around and had long ago forgotten what it was like to step in this place for the first time.

One group of such foragers, three generations of women, caught my attention as they appeared to have recently stepped out of a reality TV show. The most made-up, dyed, and glittered of the three was the oldest and she was throatily giving voice to a point of view, something even more important than their sortie from the camera frame in search of cheap chips, it seemed. The youngest, bursting with attention-getting energy, talked a mile with every step, bouncing and clinging doggedly. The woman between them, both daughter and mother, tried and failed to balance the others’ needs, unable to cap or re-direct the youngest’s activity while responding to the wise words issuing from the botoxed lips on her other side. I desired to follow them, listen and learn, but I imagined some security guard in a darkened room seeing me and tagging me for a creep and I went the other way.

Then there were the almonds. I don’t know why it sticks in my mind that there were so many almonds. Five-pound bags of them, a long aisle of head-high stacks, the top of each one threatening to tumble out onto the head of any shopper unwise enough to brush too close by. Seeing the jeopardy I was in, I trotted safely past and rounded a corner only to face a latex-gloved staff person, the first I’d seen, whose object was to get me to try a breakfast cereal being sold in boxes the size of a delivery van. Grateful for the training a city of any size gives one for this sort of thing, I avoided eye contact and kept moving.

Next, I spied a wall of freezers, glass-doored and full of icy oven cuisine. While curious to see what sort of thing might be sold in extra large jumbo family-size frozen vessels, chests, and baskets, my inquiries were cut short and my attention re-directed by my sister.

The cat litter.

It was, by comparison to the plenitude of almonds, a diminutive section, only partially compensated by the absence of any box or bag weighing less than 20 kg. Using knees as much as possible, I hefted a weighty cube into a cart, feeling smug as I evolved from observer to participant, and we moved to find the way out, on the way running across ever more randomly-associated displays, furniture next to potatoes next to watch straps.

The check-out lines required no assessment, as each was more or less the same length as the ones beside it, but we paused long enough for me to peer into the near distance. There, on the way out, a dining area, where white picnic tables were covered by white umbrellas underneath the white ceiling. It was an oasis of sensory deprivation, where people might enjoy a hot dog and coffee shaded from the stadium lighting above, a brief respite before facing the death race from the parking lot to the gas pumps, where the cheapest fuel in town was causing lines and tempers to stretch out of all reasonable proportion.

So, yes, it was more interesting than I thought. But as I write all of this down, I have to admit to using some license. A little lie or two.

No actual pyramid of pyjamas. It was a stack of jeans, but the pyramid was so much more pleasing to write. No death race for gas, but many cranky rude drivers. No watch straps, but lots of watches.

The family was real, though, but I can’t independently confirm the botox. And the almonds were there. And the eating area. I have pictures of that last one.

It’s a good lesson, though. You have to experience and observe before you can get away with describing or implying. But the role of imagination is to make it more interesting. More engaging, more fun to subvocalize, and I daresay more, not less, accurate.