If something, or someone, is too good to be true then …

You know.

Why then, are so many protagonists in best-selling novels so unbelievably good?

I have been writing a thriller, a broad sort of genre that means I am focussing a lot on a plot that is fast-paced. Characters are still important, though, especially as every thriller needs a good conflict or two and characters are our windows into all conflicts from geo-political bust-ups to a scrap between neighbours.

As I am supposed to read market-oriented thrillers because I am sort of trying to write one (it’s one of the rules you see all the time), I’ve spent some time grappling with a variety of protagonists with whom I am having some trouble.

Often, I am expected to care about a character who is presented as being rather impossibly … well, good. Rugged survivors, brooding yet humourous, tough but fair, patriotic (if they’re American but then they also have to have some kind of background in the military or love guns or both), dog loving, an imperfect parent (because that’s the only kind), insightful, thoughtful yet spontaneous, there they stand, signalling their virtue with every every line they utter, every observation they make.

Also, to my horror, authors use the word “savvy” to describe them.

Don’t get me started about that word.

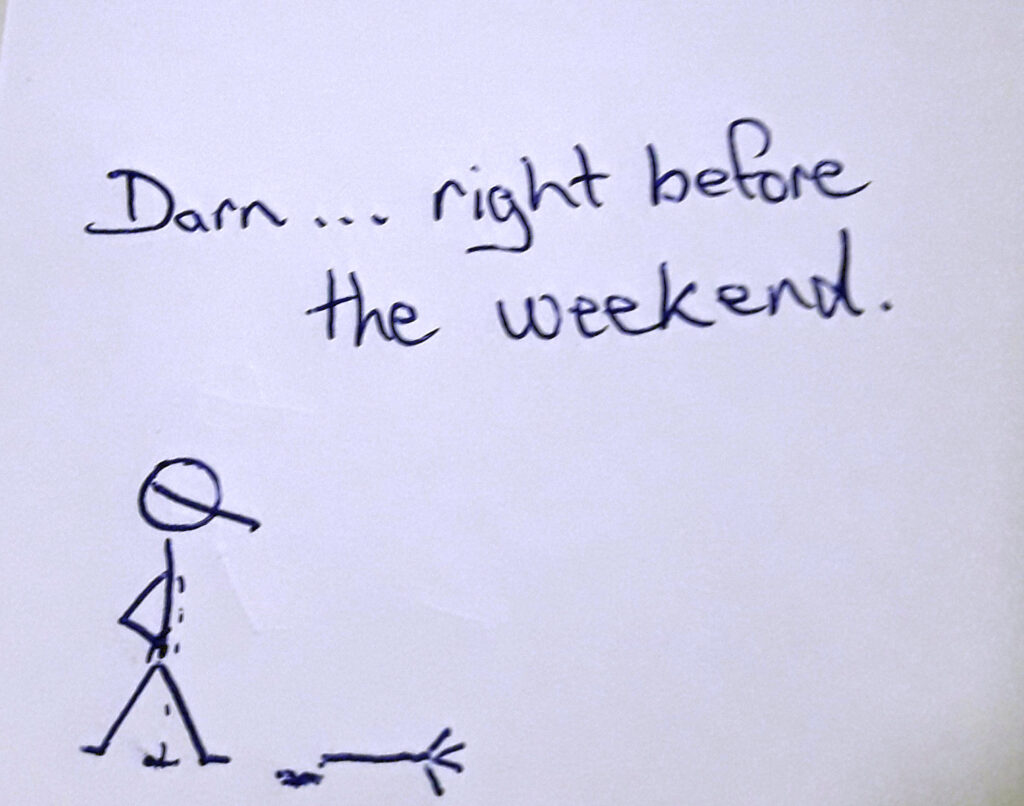

Anyway, I must also point out that we are usually shown just a wee flaw that we don’t have to look too hard to see. They have a blemish or even two. Not arrogance, because arrogance does not seem to be a blemish, given its ubiquity in pop culture heroes.

My stomach is getting unsettled just thinking about them. And they crop up in the work of best-selling authors all the time. Actually, it’s probably one of the reasons the books sell so well.

What does that say about the writing problem, meaning the fact that it’s easy to write but hard to get someone to read what you’ve written?

Do my protagonists have to be so dang-nabbed good that I hate them and myself for writing them?

Self-loathing is not why we get into this game, at least not most of us. But the sort of self-loathing that sells has to be on the page, not simply a result of having written. What good is cringing dark hatred of oneself if it doesn’t bring in a royalty cheque?

I know I am being unfair. There are lots of loathsome anti-heroes, quirky unreliable narrators and fundamentally, fatally flawed protagonists out there. I am just not sure how they ever got published.

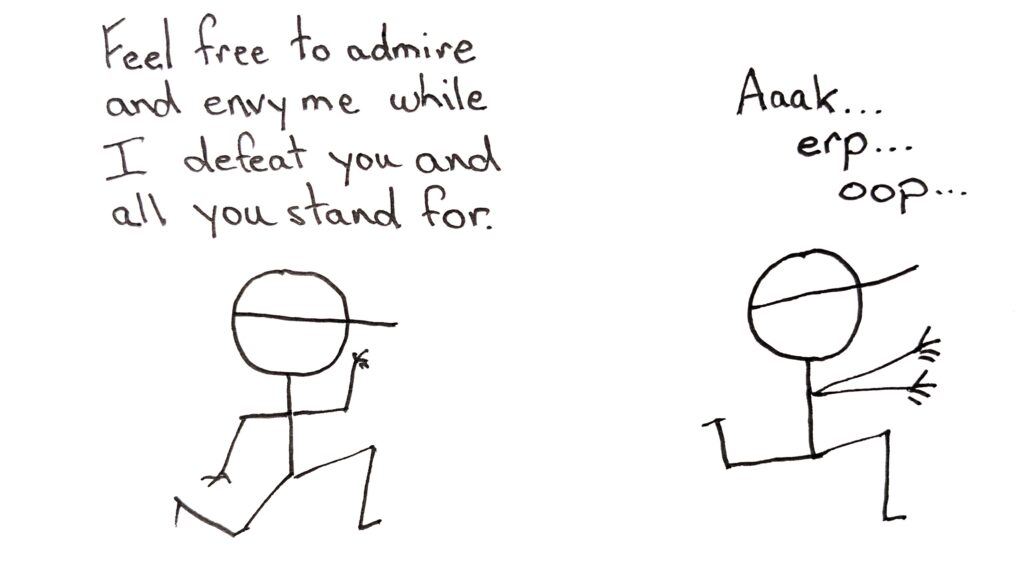

How about a protagonist who is mostly sympathetic but makes big mistakes and is conflicted all the time about hard choices? Someone who dwells in the space between the rock and the hard place and makes character-based mistakes in judgment is surely more interesting than someone who simply confidently faces problems in succession and makes the best decisions based on the information they have while punching, escaping, or otherwise outsmarting bad guys.

Naah.

Give ‘em what they want.

Troy Storm, veteran of a forgotten foreign war, PTSD survivor, runs a non-profit dog-rescue, step father to an adored eight-year-old girl whom he teaches to shoot a pistol (only in self-defence of course), partner of a savvy no-nonsense kindergarden teacher who kick-boxes to raise money for orphans in El Salvador, moonlights as personal security to visiting foreign dignitaries … .

From there it writes itself when you factor in a really bad guy.

See Bad to the Bone.

Done.