I made a mistake yesterday. I watched a movie from about twenty-five years ago. It was called A Perfect Murder, and what became clear as I watched was that nothing was in any way perfect about this film. Including the murders. And attempted murders.

Besides the plot holes and the poor direction (where’s the suspense?) the characters were what really got my attention.

There kind of weren’t … any.

Please bear with me as I rant.

The protagonist, played by Gwyneth Paltrow, is supposedly in some progressive United Nations job (she mentions the word refugees as a way of signaling her deep commitment to humanity) dressed in a fur coat and five-hundred-dollar shoes, a job which seems to allow her extended lunches a couple of times a week so that she can go off to have nooners with her arty boyfriend is his ridiculously huge studio.

What becomes evident is that, far from being likable, hateable, relatable in any way, she has no character at all. Beyond her ability to part her lips just so when she is trying to appear frightened, surprised, perplexed, sympathetic, aroused, or whatever, a store mannequin could fill in. Now, it would have to be from a posh, exclusive store, because our protagonist is just about as white, as privileged, and as rich as a person can be.

Her husband is the malevolent Michael Douglas, who also has little or nothing that might be counted as character except that he’s … malevolent. He looks good in layers of expensive clothes, and likes to comb his hair back, and if that’s not a clue to deep-seated complex and fascinating personality pathologies, I don’t know what is.

Anyway, he plots to kill Gwyneth using her boyfriend as the blunt instrument. Having found out about the artist’s shady criminal past and about the quality lunches available in Manhattan to UNO personnel, he threatens and bribes the boyfriend to turn on Gwyneth so that hubby can inherit her birthright, a fortune of about a hundred million.

The boyfriend, Viggo Mortenson, threatens to have character when we find out that he learned to paint in prison (is that even a thing?) and he likes to hook up with rich women and walk away with more than their deep appreciation. Later on, when he thinks poor Gwyneth is dead (having hired his inept buddy from prison art school to do the deed for him) he seems distraught. Later, finding out she’s alive and kicking, he seems happy as a clam to leave town for good without her. So, his character is … whatever?

Movies don’t have lots of time for character development, but we should like somebody shouldn’t we? Why cheer for the heroine who is simply exceedingly privileged?

Should we like her just because her husband’s a bonafide member of the Capitalist-Killer fraternity?

Because she has bad taste in lunchtime wrestling partners?

The film shows us nothing else about her but for the fact that she speaks a little Arabic, which is supposed to be some other signal of her all-around terrificness.

A police detective, played by David Suchet, shows up and we are briefly hopeful that an actual character has arrived, as his face demonstrates more complex elements in the first ten seconds on-screen than anyone else does in two hours. But his part is tiny and completely without effect on the plot. A waste.

Who cares, though? It’s a lousy twenty-five-year-old film. Why did this bother me?

What must have been happening was that the director and writer were thinking that just drawing an outline of a rich attractive woman with a New York job would get an audience to like her and cheer for her. And that’s the problem. Assuming an audience’s good will. Big mistake.

Assuming a reader’s, or an audience’s good will or support for a character has to be fatal. We have to have a reason to care. If your protagonist is going to save the universe, we better care about them over and above the saving part.

We are readers.

We’re safe at home.

We don’t need to be saved. What we need is to read about or watch someone interesting. And that is one of the biggest challenges of writing fiction – we have to make readers care without falling into trope or cliché.

The finest prose imaginable will not make me want to read about someone I don’t care about. It would be a terrible mistake to assume any reader of my work would be different.

People don’t want to read simply because I want to write.

Damn!

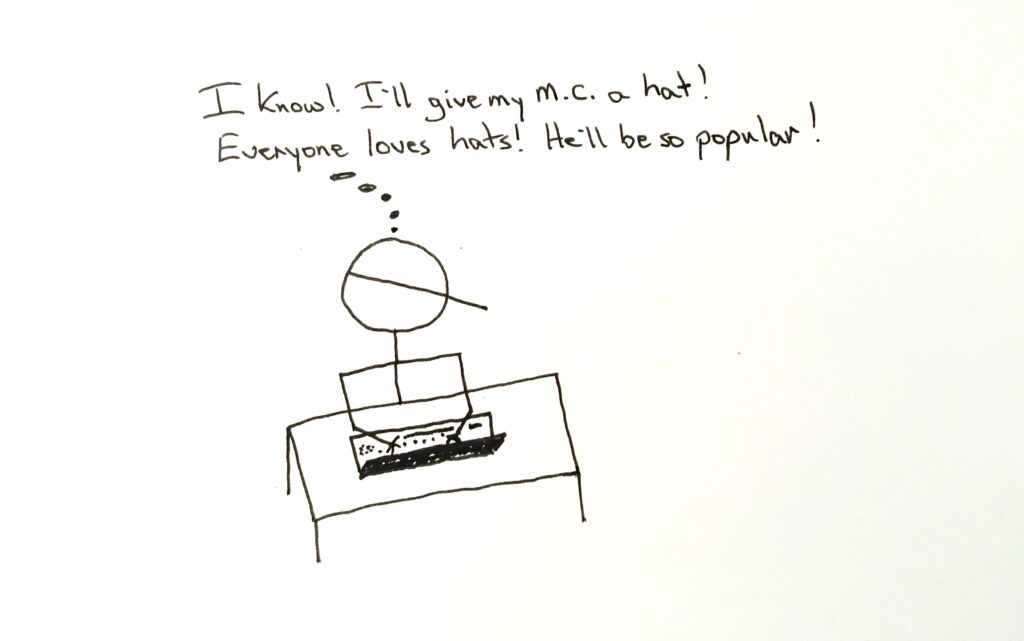

So much work.